Commentary on 1 Corinthians 11:23-26

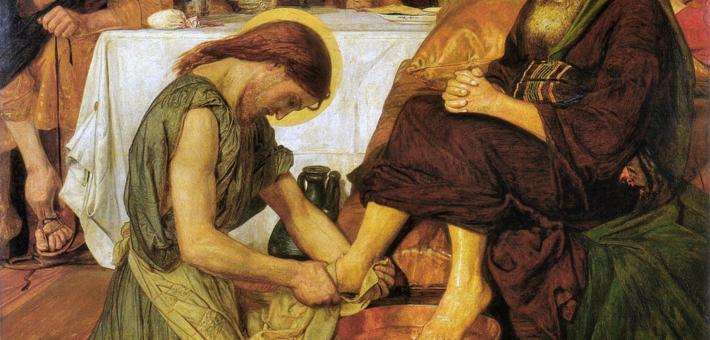

This holy day, Maundy Thursday, marks the beginning of the most consequential moments in our tradition. On the evening of this day Jesus and his first followers share the meal—the Passover meal in the Synoptic tradition—we call the “Last Supper” before going to Gethsemane, where Jesus is arrested.

The “Lord’s Supper” and divisions among Corinthian believers

Quite soon after Jesus’ resurrection, as his followers carried forward God’s good news in Jesus’ name, they began reenacting this Last Supper so that it became the primary ritual and act of worship that they shared regularly together. When Paul wrote this letter to Corinthian believers in the early 50s of the first century, he could remind them of what he’d already taught them about the ritual (verse 23). Thus we learn that observance of the “Lord’s Supper” (see 11:20) was likely established practice among believers just 20 years after Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Paul wasn’t, however, writing instructions to Corinthian believers because they’d forgotten the proper observance of the Supper. Nor was he writing a theology textbook regarding any of the issues he discussed with them, including the Lord’s Supper. He was addressing their practice in a letter that he wrote in a world where writing materials were expensive, most people couldn’t read, and no postal service existed. Consequently, there had to be a critically important reason to go to the expense and trouble of creating a letter and getting it to Corinth, where it would be read aloud to believers. Paul tells us the good reason for this letter in 1:10—the Corinthian believers were badly divided.

Division among them actually isn’t surprising. The first-century Mediterranean world under Roman rule was strictly divided along racial/ethnic, class, and gender lines, which was most clearly demonstrated in their table practices: People only ate with others like themselves. But believers, following Jesus who “ate with tax collectors and sinners,” welcomed “Jew and Greek, slave and free, male and female” into the faith community and declared they were “all one in Christ Jesus” (see Galatians 3:28). Oneness, however, was easier proclaimed than practiced.

Just prior to the lectionary reading for today, Paul has reprimanded wealthier Corinthian believers for their observance of the Lord’s Supper (11:17–22). To understand why he was so disturbed we must remember there were no church buildings at this time. Believers gathered in small groups in homes (house churches) throughout the city. Apparently, one of the higher-status believers hosted the whole community at times, probably because his house had space for all of them. But this host also seems to have invited other high-status believers to his home for a sumptuous supper prior to the arrival of everyone else.

These believers may not have thought they were doing anything problematic. They probably weren’t mean people and didn’t intend to be hurtful. In fact, they may have thought that issuing an invitation to poorer members would be insulting for those who wouldn’t have been able to reciprocate, given that such reciprocity was expected of honorable people in this culture. So their earlier, separate meal may have seemed “normal” for them.

But Jesus’ movement challenged what had been “normal” precisely because of what happened next. When the other believers arrived, some of whom were so poor that they were hungry, they experienced the humiliation of being “not worthy” of a place at the table yet again (see 11:21–22). No wonder Paul declared they were not eating “the Lord’s Supper” (11:20; emphasis mine).

Paul’s instructions in this moment

Paul responded to this situation by calling to mind what they were to remember when they shared the Lord’s Supper: Jesus gave himself “for you” (verse 24). While we often assume that Paul refers to Jesus dying for our sins, in the divided Corinthian context he may be pointing believers toward Jesus’ practice of including everyone at his table as a primary reason that Rome broke his body and shed his blood. In an intentionally segregated world, his table practice was revolutionary. As New Testament scholar Robert Karris once said, Jesus basically died because of how he ate.

Such a perspective fits Paul’s assertion that sharing the Supper enables us “to proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (verse 26). Jesus declared that God’s kingdom has drawn near (not future tense) and believers share in it now. And when it comes in its fullness, then people “will come from east and west, north and south” to sit together at God’s table (see Luke 13:29), as many of us say in our Eucharist liturgies today. Thus, when “Jew and Greek, slave and free, male and female” sit together to share bread and wine, they reenact Jesus’ transforming practice of welcoming and valuing everyone while they look forward to God’s ultimate gathering of all people to share God’s feast (see Isaiah 25:6–8).

Such a perspective also fits with Paul’s following claim that “all who eat and drink without discerning the body, eat and drink judgment against themselves” (11:29). Let’s note his concern for “discerning the body” and then observe that Paul will address at length the church as the “body of Christ” in the following chapter (1 Corinthians 12). Among many nuggets of wisdom in that text is his stress on the “one Spirit” who gives all gifts for the purpose of building up the one body of Christ (12:4–7, 12–13), all of which means our diversity is necessary if we would be the body of Christ (12:14–17). Furthermore, if we hope to function as a healthy body, then the body’s different members must work together and care for one another (12:25–26).

How, then, might Paul answer if we asked, “When you said ‘discern the body,’ did you mean that the Corinthian believers should remember that the bread they share evokes the broken body of Jesus who gave himself for others? Or did you mean that the believers should remember that they belong to the ‘body of Christ’ so that how they treat others matters greatly?” I suspect his answer would simply be, “Yes.” Eating the “body of Christ” and being the “body of Christ” were intertwined for Paul and should be for us. This teaching seems particularly relevant as white supremacy and the scapegoating of immigrants are on the rise in the United States.

April 17, 2025